11 Indian Cooking Techniques That Change the Flavor

If your idea of Indian food is "just a lot of spices," this guide will widen that view. The same spice can taste different depending on how you treat it. In many homes, dadi’s small actions—tossing cumin in hot oil, letting yogurt sit on the counter—are the real flavor makers. This post explains eleven techniques that shift aroma, depth, texture, and brightness. You’ll get short explanations of the science behind each method, simple steps to try at home, regional notes, and common pitfalls to avoid. The goal is practical: pick one technique to practice each week and notice the difference.

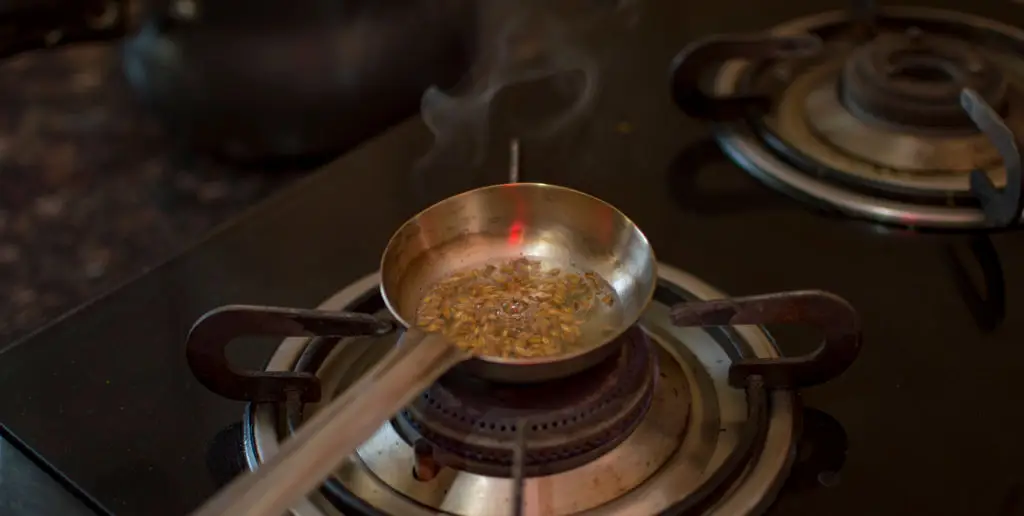

1. Tempering (Tadka)

Tempering—called tadka or chhonk—is when whole spices sizzle in hot oil or ghee to release their essential oils. A quick heat burst transforms dry seeds into aromatic flavor carriers that then perfume the entire dish. Start with a smoking-hot pan, add oil or ghee, then whole spices like cumin, mustard seeds, or curry leaves. The seeds should pop or darken slightly. Short timing is key. If spices burn, they become bitter. Tempering can be used at the start to flavor the cooking fat or poured over a finished dal to give a final aromatic lift. In South India, a tadka might include red chilies and curry leaves. In Bengali kitchens, nigella and mustard seeds are common. The technique works well for quick weekday dals and yogurt-based raitas. Tip: keep a small spoon of oil hot and test one seed first to learn the right tempo. For safety, tilt the pan away from you when adding wet ingredients; steam can jump. This small, fast step often makes a simple dish feel finished and homey.

2. Dry Roasting (Bhunna)

Dry roasting concentrates and deepens spice flavors by driving off surface moisture and encouraging mild browning. Whole spices like coriander, cumin, and fennel gain nuttiness and a warmer aroma when gently toasted in a dry skillet. Heat a heavy pan over medium heat, add spices in a single layer, and stir constantly until they become fragrant. You’ll see a slight color change and smell toasted notes. Cool them before grinding for a fresher, richer masala than store-bought powders. Roasting also reduces grassy or green edges in some spices, making blends smoother. Regional kitchens roast seeds for specific mixes—Garam masala in the north often starts with roasted spices, while certain lentil dishes in the south use roasted coconut along with spices. Don’t rush the process with high heat; rapid charring causes bitterness. Store freshly roasted and ground spice blends in airtight jars away from light. Small batches last longer and taste brighter than pre-ground commercial spices.

3. Grinding Fresh Spices

Grinding whole spices just before use preserves volatile oils that diffuse quickly once exposed to air. A short grind in a spice grinder or a rhythmic pound with a mortar and pestle keeps flavors alive and layered. Wet masalas—blends of roasted spices with aromatics and oil—create a bright, immediate flavor that bottled powders can’t match. For a quick homemade masala, combine roasted coriander, cumin, and dried red chilies, then grind coarsely. The tool matters. Mortar-and-pestle grinding releases a different texture and aroma than electric grinders, because the crushing motion bruises ingredients without heating them. Use a small electric grinder for efficiency, but reserve hand grinding for finishes like garam masala or green chutneys. Freshly ground spice blends lift simple dishes like stir-fries or quick dals. Keep whole spices on hand and grind in small batches—this simple habit leads to clearer, fresher flavors in everyday cooking.

4. Slow Cooking (Dum)

Dum cooking traps steam and aromatic compounds inside a sealed vessel so flavors develop slowly and integrate deeply. The technique typically uses low heat and a tight lid; sometimes, dough or foil seals the pot to hold steam. Slow, gentle heat softens tough cuts of meat and helps rice absorb spiced cooking liquids without losing separate grains. In biryani or slow-cooked stews, dum turns layered spices into a unified, complex profile. Scientifically, lower temperatures promote collagen breakdown in meats and allow volatile spice molecules to disperse evenly through steam. If using dum at home, assemble ingredients hot, seal the pot well, and keep the heat low to avoid burning. Modern ovens or sealed Dutch ovens can replicate the effect if you lack traditional handiwork. Dum favors ingredients that benefit from long contact with aromatics—root vegetables, lamb shanks, and tightly packed rice dishes. The result feels more soulful and balanced than rapid, high-heat cooking.

5. Smoking Technique (Dhungar)

Dhungar is a quick smoking method that adds a controlled charcoal aroma without long smoking equipment or time. A small piece of lit charcoal is placed in a metal bowl inside the dish; a drizzle of ghee or oil and a tight lid trap smoke long enough to infuse flavor. Smoke introduces phenolic compounds that the brain reads as savory and rustic, giving dals, paneer, or kebabs a restaurant-style finish. Use caution: light the coal outdoors or over a gas flame, then transfer carefully. Remove any ash before covering the pot. The smoke step is short—often only a minute or two—too much smokiness can overpower. Regional cooks vary the fuel: coconut shell or dried wood can offer different smoke notes. Dhungar is ideal when you want a deep, charred note without searing or long smoking sessions. For home cooks, practice on small batches to find the balance you like.

6. Oil and Ghee Infusion

Fats are major flavor carriers: they dissolve and hold aromatic molecules that water cannot. Infusing ghee or neutral oil with spices, garlic, or chilies creates a concentrated aromatic base you can use across dishes. Warm the fat gently with aromatics until they release aroma, then cool and strain. Spiced ghee added at the end brightens textures and makes breads, rice, and dals more luxurious. Because fats trap volatile compounds, infused oils deliver a long-lasting aroma and mouthfeel. Ghee adds a nutty, buttery richness and tolerates higher heat than butter, making it useful for both cooking and finishing. Infused oils also preserve better than wet pastes when stored correctly in sterilized jars. Use small quantities for finishing dishes, or spoon a little into plain rice or khichdi for an instant lift. Keep infused fats refrigerated if you include fresh aromatics to prevent spoilage.

7. Layering Spices

Layering spices means adding different spices at set times during cooking so each one contributes a distinct note. Start with whole seeds in hot oil to flavor the fat, then add powdered spices mid-cook so they toast into the sauce, and finish with fresh herbs or garam masala to preserve volatile aromatics. This staged approach makes dishes more three-dimensional than adding everything at once. Timing controls chemical reactions: early heat encourages slow compound release; later additions preserve freshness. For example, turmeric and ground coriander benefit from a short sauté to remove raw edge, while fresh cilantro or garam masala should be added off heat. Many regional cooks follow an instinctive sequence—watching color and aroma—so try following a simple order and refine it by tasting as you cook. Layering makes busy weekday curries taste thoughtful without extra effort.

8. Acid Balancing

Acids brighten heavy or rich dishes by lifting flavors and creating contrast. Indian kitchens use tamarind, lemon, kokum, raw mango, and yogurt to add tang and cut through fat. A small splash at the end can change the entire impression of a curry, revealing hidden spice notes and making the dish feel lighter. Acids also help balance sweetness and salt. Add acids cautiously: start with a teaspoon, taste, then adjust. Yogurt added too early can curdle on high heat, so stir it in at lower temperatures or temper it first. Tamarind paste dissolves into gravies during cooking and gives a deeper, fruitier tang, while fresh lemon adds a sharp, citrus top note. For drinks and chutneys, acid becomes the central flavor. Learning small amounts and timing creates bright, balanced dishes instead of flat or overly rich ones.

9. Marination with Enzyme or Rich Carriers

Marination does more than season: acids, enzymes, and fats help flavor penetrate and alter texture. Yogurt-based marinades add creaminess and mild acidity, while papaya or pineapple contains enzymes that tenderize tougher proteins. Salt in a marinade draws moisture and helps other seasonings soak in. For best results, marinate in the refrigerator and avoid excessive enzyme exposure that can make meat mushy. Use thicker carriers like yogurt or oil to hold spices against food; thin, very acidic solutions work faster but can over-soften. For vegetables, short marination improves flavor without changing texture. Remember food safety—marinate in covered containers and discard used marinade or boil it before using as a sauce. Marinades are a practical way to introduce layered flavor before cooking begins and make grilled or roasted dishes deeply flavored rather than relying on surface coating alone.

10. Fermentation (Batter and Fermented Foods)

Fermentation transforms raw ingredients through beneficial microbes, producing acids, gases, and flavor compounds that shift texture and create complex sour and umami notes. In South India, fermented rice and urad dal batter yield fluffy idlis and tangy dosas with a mild, lifted aroma. Fermentation also enhances digestibility and creates depth unavailable from direct acid additions. Control temperature and timing for reliable results; warmer climates speed fermentation, while cooler homes need longer resting times or a warm spot near the oven. Small changes in batter hydration and inoculum (a spoon of old batter) affect sourness and texture. Fermented condiments and batters are a practical way to build layered flavors over days rather than minutes. For home cooks, start with a small batter batch to learn notes and consistency, and adjust resting times to match your kitchen’s climate.

11. Pickling and Achar Techniques

Pickling concentrates flavors through salt, oil, and acid, producing sharp, long-lasting condiments that punctuate meals. Indian achar includes raw mangoes, lemons, and mixed vegetables preserved with spices, mustard oil, and salt. Sun-packed or cold pickling methods both create depth, though timing and heat vary by region. Over time, flavors meld and intensify, adding bright, spicy bursts to rice, curries, and snacks. Pickling also extracts and intensifies spice flavors as the vegetables cure. Use clean, dry jars and follow safe salt ratios to prevent spoilage. For quick pickles, a short soak in vinegar and spices will give a fresh, tangy counterpoint to richer dishes. Achar is a practical home strategy: make small batches to find the balance of heat, sweetness, and sourness you prefer. These preserved bites are often the final flavor punch that keeps meals memorable.

Wrap-Up: Practice the Techniques, Notice the Difference

Techniques change flavor as much as ingredients do. Small rituals—tempering a spoon of cumin, toasting whole spices, or finishing a pot with dhungar smoke—shift aroma and depth dramatically. Try one technique a week, beginning with tempering or dry roasting, to notice immediate differences. Keep a simple notebook: note timing, heat level, and the dish you used, then adjust. Over time, you’ll develop an internal rhythm like many home cooks and dadi figures who learned by tasting and adjusting. These methods work with everyday ingredients and modest equipment. You don’t need rare spices—just practice, freshness, and patience. If one method overpowers a dish, tweak the timing or quantity next time. Share results with friends to compare notes; regional variations mean useful tricks thrive in different kitchens. With a handful of techniques in your repertoire, you can deepen flavor and make weekday meals taste like something special.